How not to drop dead

A 38-year-old man was recently brought into my emergency department unresponsive. He had suddenly collapsed at home, and we weren't able to revive him. As family and friends arrived at the hospital, I heard them say to one another, "We don't know what happened – he just dropped dead."

How does this happen? How can someone who is alive and well one moment "drop dead" the next?

By the end of this post, you'll understand how, and learn steps you can take now to decrease the chances of it happening to you or someone you love.

The big five that keep us alive

When a person dies unexpectedly and suddenly, it's nearly always because of a problem with the big five that keep us alive:

- Pump

- Pipes

- Air

- Blood

- Brain

What could go wrong?

What can go wrong in each of these categories? Major failures are fortunately uncommon, but they are catastrophic when they do occur.

We'll talk about the pump last, because it's by far the most common to fail. Here are the major things that go wrong in the other 4 categories:

| What most commonly goes wrong | ||

|---|---|---|

| 2 | Pipes | A blocked or torn major blood vessel, such as a pulmonary embolism or aortic dissection. |

| 3 | Air | Not enough oxygen or not breathing. Choking, drowning, suffocation. Includes drug overdose, which most commonly causes death by causing someone to stop breathing. |

| 4 | Blood | Losing too much blood. For example, from an injury such as a major car accident. |

| 5 | Brain | A stroke, particularly hemorrhagic stroke. |

The pump

The pump we're talking about in the human body, of course, is the heart. A sudden stop in the pumping action of the heart is the most common cause of sudden death.

That is, the pipes, air, blood, and brain are fine, but the darned pump just stopped pumping.

Overwhelmingly, the primary cause of sudden death is a pump problem.

You're talking about cardiac arrest, right?

The term cardiac arrest means simply "the heart has stopped pumping." It tells us nothing about why.

It may seem like circular logic to say that someone died because their heart stopped pumping, and indeed a person's heart must stop for them to be declared dead. In fact, every dead person has suffered cardiac arrest – their heart has stopped. So it doesn't shed much light to say someone "had a cardiac arrest."

However, there's an important distinction to be made between someone who first suffers a problem with the pipes, air, blood, or brain, and someone whose primary problem is a pump problem.

Why does the pump stop?

So we understand that everyone who dies ultimately has cardiac arrest ("stopped heart"), but the most common reason the heart stops pumping is that the pump itself stops working.

Overwhelmingly, the most common reason the pump stops working is because of an electrical problem.

An electrical problem?

You see, in a human heart, there is internal "wiring" that connects the pump's components together. If this wiring is broken, the pump's component's can't work together and the pump can't... well... pump.

And now, a 60 second detour to explain the electrical system of the human heart.

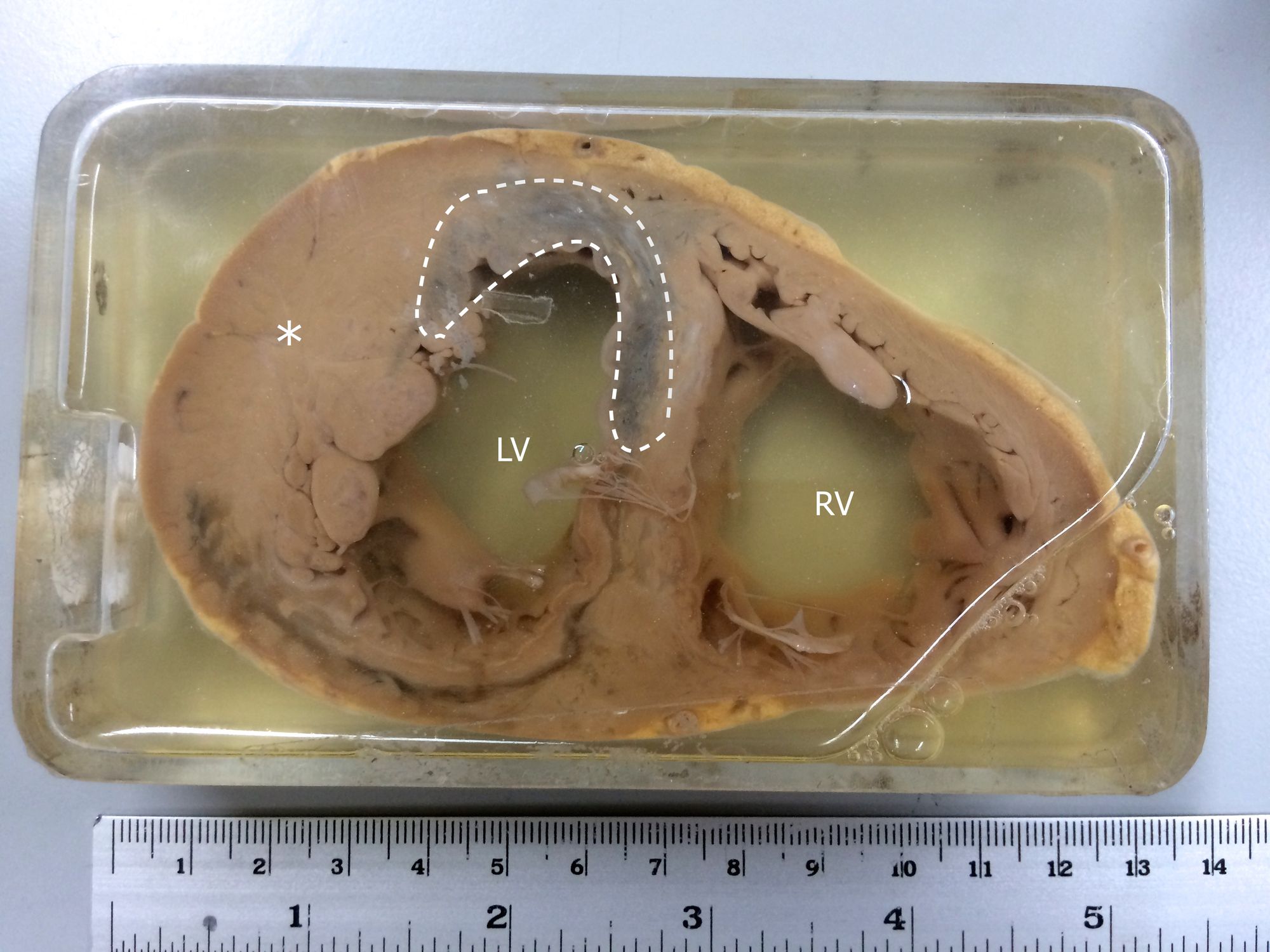

How a human heart works

There's a group of cells at the top of your heart that generate a tiny "spark" of electricity that causes your heart to beat. These cells, called the pacemaker cells and located at the sinoatrial node, begin firing in a human around 6 weeks after conception and usually don't stop until a person dies.

The electricity generated by the pacemaker cells spreads through the atria (the smaller chambers of the heart), causing them to contract, and then through the ventricles (the larger chambers of the heart), causing those to contract.

The atria and the ventricles contracting in sequence cause the "lub-dub" sound that we call a heartbeat.

We can detect the spread of electricity from the pacemaker cells through the rest of the heart, and draw a diagram of that electrical impulse. I bet you've seen it:

When a heart stops pumping, it's most commonly because of a problem with this electrical "signal" and the spread of electricity through the heart. Without the electrical impulse to direct it, the heart cannot squeeze, and therefore cannot pump.

That's why we always see doctors looking at tracings of the heart's electrical system, known as a rhythm strip or electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG). Because the heart is first and foremost an electrical system, if the electrical system is working normally, there's a good chance the mechanical system (pumping action) is working too.

What about heart attacks?

In a heart attack, a blockage in the arteries of the heart (coronary arteries) causes part of the heart's muscle to die. The technical term for a heart attack, myocardial infarction, literally means "dead heart muscle."

That dead heart muscle does a poor job of conducting electricity, wreaking havoc on the heart's exquisitely tuned electrical system.

When someone dies suddenly of a heart attack, it's most often because dead or dying heart muscle caused a sudden electrical problem in the heart, and the electrical problem caused the pump to stop.

Clear!

Now you're beginning to understand why everyone who nearly dies on a medical TV show is brought back to life with an electric shock and someone yelling "clear!"

When the heart stops because of an electrical problem, it can often be fixed with electricity.

Let's look at when and how this is the case.

The shockable rhythms

Not all electrical failures in the heart can be fixed with electricity. Lucky for us, however, the two most common electrical problems are the very two that can be fixed with electricity! [1,2]

Remember the normal electrical heartbeat tracing above? Take a look at these two. Something's not right.

These rhythms are ventricular fibrillation (VF) and ventricular tachycardia (VT). In VF and VT*, the organizing rhythm of the heart is gone, and replaced with disorganized electricity that can't keep the heart pumping. ("Fibrillation" means the ventricles are vibrating in a disorganized way, while "tachycardia" means they are going very fast.)

An external shock to the heart, known as defibrillation, can stop VF and VT and shock the heart back to its normal rhythm, thereby fixing the pump and saving a life.

CPR to the rescue

A person whose heart has stopped needs 2 things: (1) pumping action, and (2) a shock to try to fix the electrical problem, if VF or VT is present.

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation, or CPR, is the set of scripted actions we take to provide these 2 crucial ingredients.

For the general public, the American Red Cross emphasizes simply calling 911 and pushing hard and fast in the center of the chest, which is called giving chest compressions.

Known as "hands-only" CPR, these simple recommendations remove the outdated "mouth-to-mouth" technique for lay rescuers. Compressions should be delivered at a rate of 100-120 beats per minute, the beat of "Staying Alive."

The Red Cross's emphasis on simply pushing hard on the chest to pump blood through the body reflects one of the core themes of this article: that a pump problem (not an "air" or oxygen problem) is the most common reason a heart stops beating.

However, while chest compressions are vital, it's often the defibrillator that provides the crucial electrical reset and restarts the heart's pumping.

Automated external defibrillators (AEDs)

For a trained rescuer, once chest compressions are in progress*, the next step is to try to shock the heart back to a normal rhythm with a defibrillator.

Defibrillators in hospitals have multiple settings and, of course, the handheld paddles you've seen used on TV (although large stickers placed on the patient's chest are used far more often than those paddles).

In the past few decades, automated external defibrillators (AEDs) have proliferated in public places like airports and malls. These devices allow anyone to provide life-saving defibrillation with minimal training. [3]

What you can do

Now that we understand the most common reasons why people die suddenly, what can you do to prevent it from happening?

Look for warning signs of an impending problem with your heart

People predisposed to electrical problems with their heart may show subtle symptoms of the problem before cardiac arrest occurs.

For example, some people have brief episodes of ventricular tachycardia (VT) that come and go, and are experienced as fainting, chest pain, or other symptoms. These episodes quickly resolve, but indicate impending cardiac arrest.

Don't ignore symptoms of chest pain, shortness of breath, passing out, feelings of your heart racing, dizziness or lightheadedness. Although these symptoms are worrisome at any time, symptoms worsened by exertion (like exercise or climbing stairs) are particularly concerning, because they could mean that your heart is not handling stress well.

Know your family history. In particular, sudden death in a close relative at a young age should be taken as a major warning sign and prompt a visit to your primary care doctor or a cardiologist.

Many young people who die suddenly have an undiagnosed or ignored underlying structural or electrical problem with their heart due to an inherited disorder.

Learn CPR

We recommend taking a CPR class, in-person or online with the American Red Cross, to become certified in CPR.

If you don't plan to take a CPR class, you should at least watch a few videos on YouTube to learn the basics of CPR. Multiple instructional videos are available from the Red Cross and other organizations.

Here's a dramatic real-life resuscitation by professional rescuers, featuring chest compressions and life-saving use of a defibrillator. It's unclear if in this video the man (A) drowned first and then suffered cardiac arrest from a lack of oxygen (an "air problem"), or (B) his heart suddenly stopped working while exercising/swimming (a "pump problem"), causing him to drown. Regardless, the successful use of the defibrillator indicates he was in VF or VT.

Buying an AED

If defibrillated within the first minute of collapse, a person's chances for survival are close to 90 percent. For every minute that defibrillation is delayed, survival decreases by 7 to 10 percent. If defibrillation is delayed by more than 10 minutes, the chance of survival in adults is less than 5 percent. [4]

Those are impressive and scary statistics. As prices for AEDs have fallen, some people have purchased them for their homes, reasoning that immediate access to an AED could be the difference between life and death.

Keeping with our philosophy at Duration Health of preparing for disasters and staying healthy when medical care becomes unavailable, we recommend you consider buying an AED for your home if you can afford one.

Is an AED worth the cost?

A New York Times article in 2008 spoke out against consumers buying AEDs, grossly mischaracterizing and misunderstanding the results of a New England Journal of Medicine study measuring the public health impact of AEDs at home.

The study in question looked only at patients with known severe heart disease who had already had a heart attack, and was not able to conclusively prove that AEDs in their homes saved lives. It may be that there were not enough people in the study to demonstrate a statistically significant effect, as the authors themselves concluded.***

AEDs do save lives. In fact, AEDs in the home saved 4 lives as part of this study.

Fascinatingly, the AEDs were used on 7 people not involved in the study, who were neighbors or visitors to the study participants homes, and one of those people was saved by an AED as well!

AEDs are an insurance policy

Buying an AED is like buying a life insurance policy that pays off in actual life, instead of dollars.

Like a fire extinguisher or smoke detector, you may not ever use it, but if you do, it will be one of the best investments you ever made.

Summary

We talked about the big five that keeps us alive: pump, pipes, air, blood, brain.

We learned how the pump is the most common point of failure, and that an electrical problem with the pump is the most common reason.

We discussed the heart's electrical system, including the pacemaker cells.

We learned about the two shockable rhythms: VF and VT.

We learned that early CPR and defibrillation saves lives.

Know the warning signs of a heart problem, and speak with your doctor about them

And, if you can, buy an AED.

Other frequently asked questions

What about atrial fibrillation?

Apple made headlines in 2018 when they announced that the Apple Watch would allow users to detect atrial fibrillation (AFib).

You might be wondering how AFib fits into the story of sudden cardiac arrest. AFib is essentially a problem with the pacemaker cells discussed earlier. As opposed to the disorganized rhythm in the lower part of the heart (ventricles) seen in ventricular fibrillation, atrial fibrillation is the same phenomenon in the upper part of the heart (atria).

AFib is not immediately life threatening, because the ventricles continue to contract, and the heart continues to pump blood. However, the irregular rhythm of AFib can cause a clot to form in the heart, which can then travel through the body clogging the arteries (a "pipes problem") and, if the arteries leading to the brain are clogged, causing a stroke (a "brain problem").

What about "flat lining"?

When someone dies suddenly on TV, the heart monitor usually emits a long beep, and a "flat line" is shown. This flat line is known as asystole (rhymes with "hey-MISSED-oh-lee"), and indicates no electrical activity in the heart.

Asystole is not a shockable rhythm, so defibrillation won't help. The treatment is CPR (chest compressions). Fortunately, it's less common than VT and VF.

What happens if you use an AED on an unconscious person not in VF or VT?

Nothing. AEDs are programmed to detect VF and VT and deliver shocks only when appropriate. AEDs are extremely safe. In an emergency, just go for it and use it – you may save a life.

About Duration Health

Duration Health helps keep you and your family healthy when medical care becomes unavailable.

Visit durationhealth.com and learn more about our prescription emergency medication kits. Get prepared today.

Footnotes

This post is not medical advice. Always seek the expertise of your healthcare professional.

* Technically, it's pulseless ventricular tachycardia that qualifies as a disorganized heart rhythm resulting in cardiac arrest, and not other forms of ventricular tachycardia. This distinction is beyond the scope of this article; we'll focus solely on pulseless VT here.

** It's debatable whether chest compressions or defibrillation should be performed first. Chest compressions and defibrillation are equally important, so ideally they should be performed simultaneously if 2 rescuers are present.

*** From the study: "...the trial had substantially less power than initially projected. These effects were so profound that even a doubling in the population size would not have been sufficient to show an overall mortality benefit with home AED therapy. Remarkably, the enrolled patients were as likely to die from noncardiac causes (37.8% of deaths) as from sudden cardiac arrest from tachyarrhythmia (35.6%), with an annual risk of sudden cardiac arrest of less than 1% per year." [5]

[1] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2872586/

[2] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29191702

[3] https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa020932

[4] https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/circ.102.suppl_1.I-60